Browser sandboxing is a security mechanism that isolates web browser processes and tabs from the rest of the operating system to prevent malicious code from exploiting vulnerabilities in the browser or the underlying system.

Sandboxing

In general, the process is basically as follows:

-

Create a separate process for the web browser. This process is usually called “parent process”. This process has permits such as writing data to the file system, accessing RAM, processor and other computer hardware. Just like a normal process.

-

Limit access to system resources. Once the sandbox is created, access to system resources such as the file system, network, and device drivers is restricted, preventing unauthorized access.

-

Run web content in a separate process. To further isolate web content, modern browsers run web content, such as web pages or extensions, in a separate process or container within the sandbox. These processes are usually called “child process”.

-

Monitor and restrict system calls. The sandboxed environment can monitor and restrict system calls, which are requests made by the browser to access system resources. This helps prevent malicious code from executing unauthorized actions or accessing sensitive information. In addition, if some websites need to access system resources, the website can access system resources via IPC (inter-process communication). This allows us to use web browsers on a daily basis without any issue.

Applying these operations differ according to operating systems. For example, in Linux, seccomp and user-namespaces feature in the kernel are used to create a sandbox. Or sandbox(7) can be used to create a sandbox in OSX.

Let’s take a closer look at some of the basic steps I mentioned above.

Creating a sandbox environment

As I said before, this process varies according to the operating system. But since it is a more knowledgeable area, I will try to explain it through Linux. The necessary information about other operating systems can be found in Mozilla or Chromium’s own documents (especially preparing this document from these two browser).

First, let’s see which technologies we can use to create a sandbox.

SUID sandbox

SUID (Set User ID) sandbox is a type of browser sandbox. It works by setting the setuid bit on the browser executable file. In this way, the program runs with the permissions of the user who owns the program’s executable file instead of the user running the program. In order to use this method, the owner of the executable file must be root.

With the elevated privileges, SUID sandbox uses various techniques such as chroot and namespaces to isolate the program’s access to file systems, network ports, and other resources.

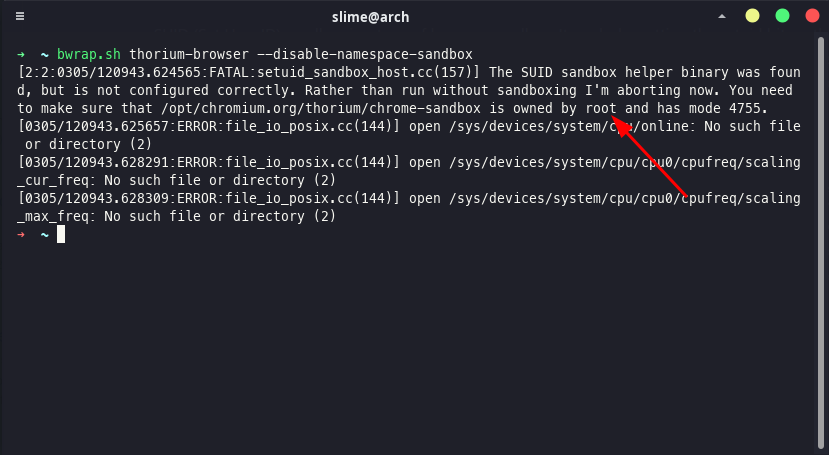

If we prevent privilege escalation, SUID sandbox will not work. For example, we can force Chromium to use SUID sandbox by giving --disable-namespace-sandbox parameter. This way, we can see how it will react in a sandbox like the one shown in the picture below.

Running Thorium Browser (optimized Chromium) inside a sandbox that does not allow elevated privileges. I am using the tool that I explained how to use in this document to create a sandbox.

Running Thorium Browser (optimized Chromium) inside a sandbox that does not allow elevated privileges. I am using the tool that I explained how to use in this document to create a sandbox.

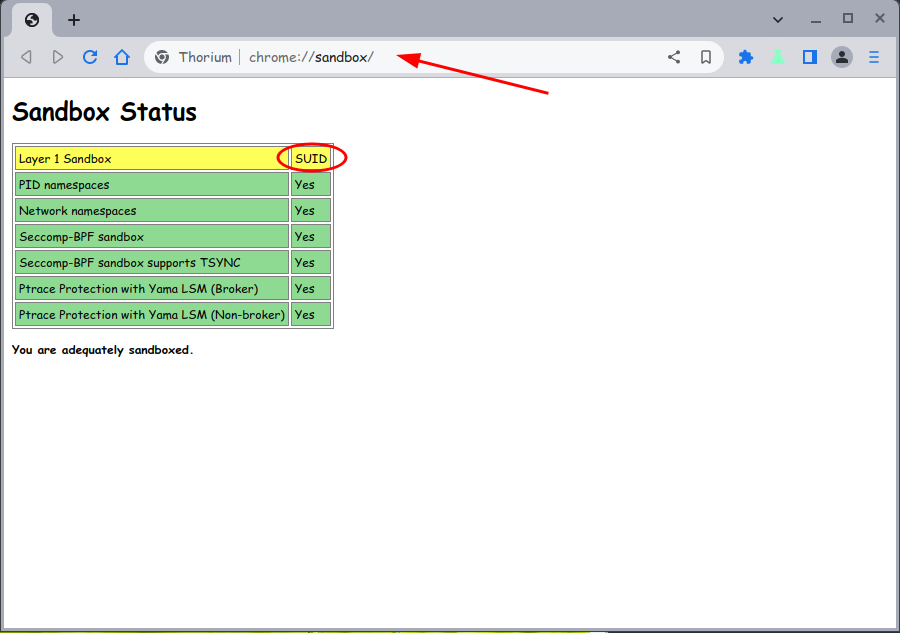

Chromium prefers to use the user-namespaces feature in the kernel instead of SUID bits (if it is available), due to several reasons, including the fact that having a setuid binary is more risky against privilege escalation attacks. These reasons, including others, are explained here.

Chromium using SUID sandbox.

Chromium using SUID sandbox.

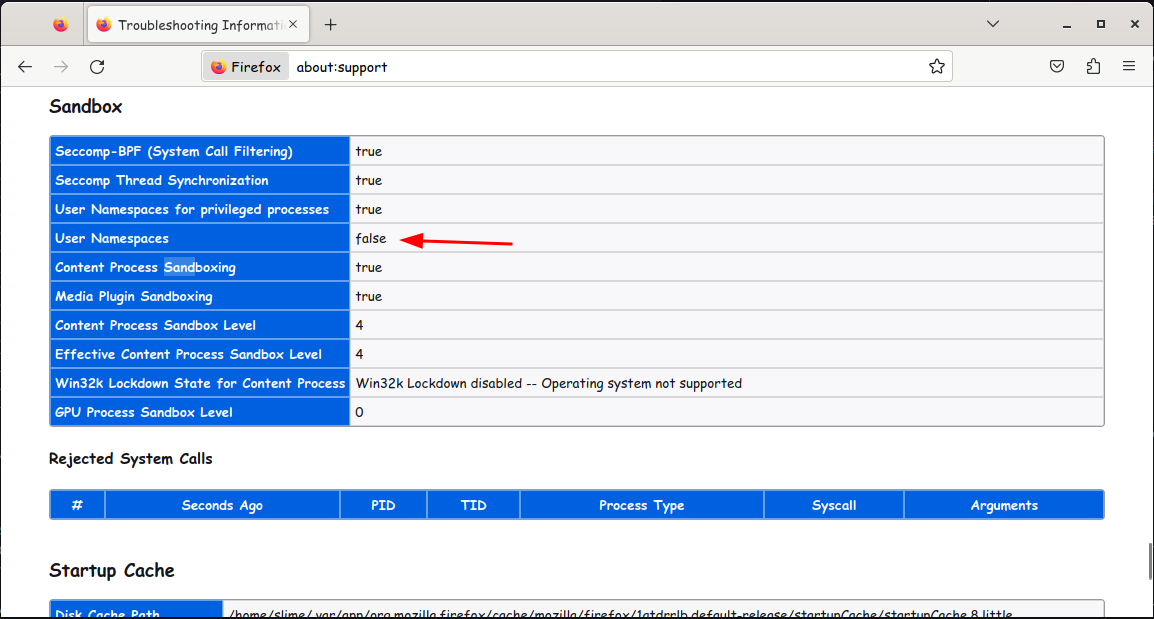

Note: Firefox does not use SUID sandbox. If user-namespaces are not available, Firefox only uses seccomp-bpf. This means that the sandbox will provide less protection as a part of it will be unusable.

user-namespaces sandbox

user-namespaces sandbox is a system that isolates system resources using the user-namespaces feature in the Linux kernel. It isolates resources such as users and group IDs, network, and file system. It does not require any administrative privileges.

It generally requires a kernel >= 3.10, although it may work with 3.8 if certain patches are backported. In addition, some distributions may choose not to use this feature in the kernel. Therefore, browsers have alternative sandboxing solutions. The SUID sandbox in Chromium is an example of this.

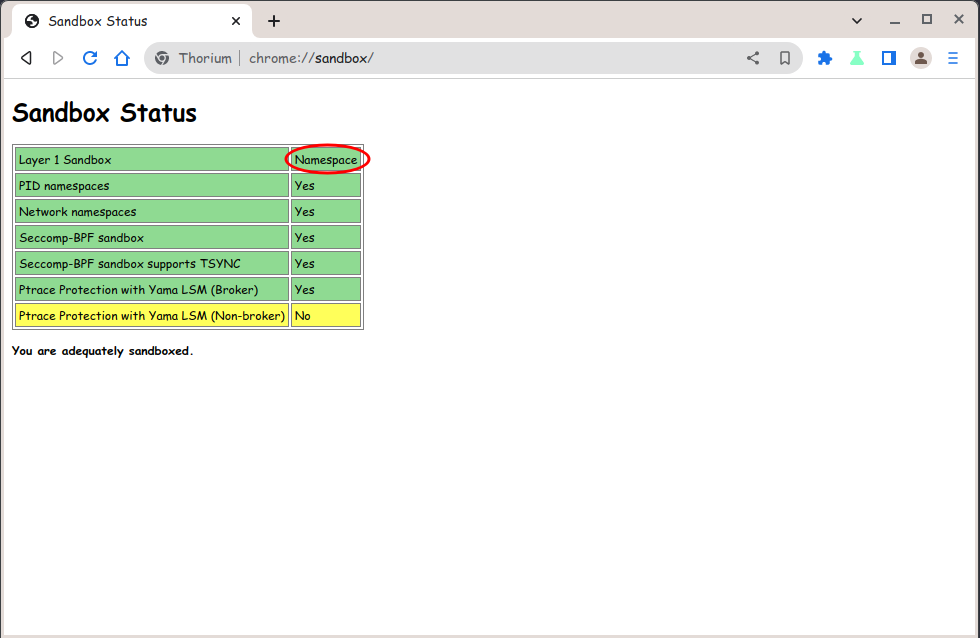

Chriomium using user-namespaces sandbox. user-namespace sandbox is default in Chromium. If your kernel supports the user-namespace feature, it is preferred over SUID sandbox mode.

Chriomium using user-namespaces sandbox. user-namespace sandbox is default in Chromium. If your kernel supports the user-namespace feature, it is preferred over SUID sandbox mode.

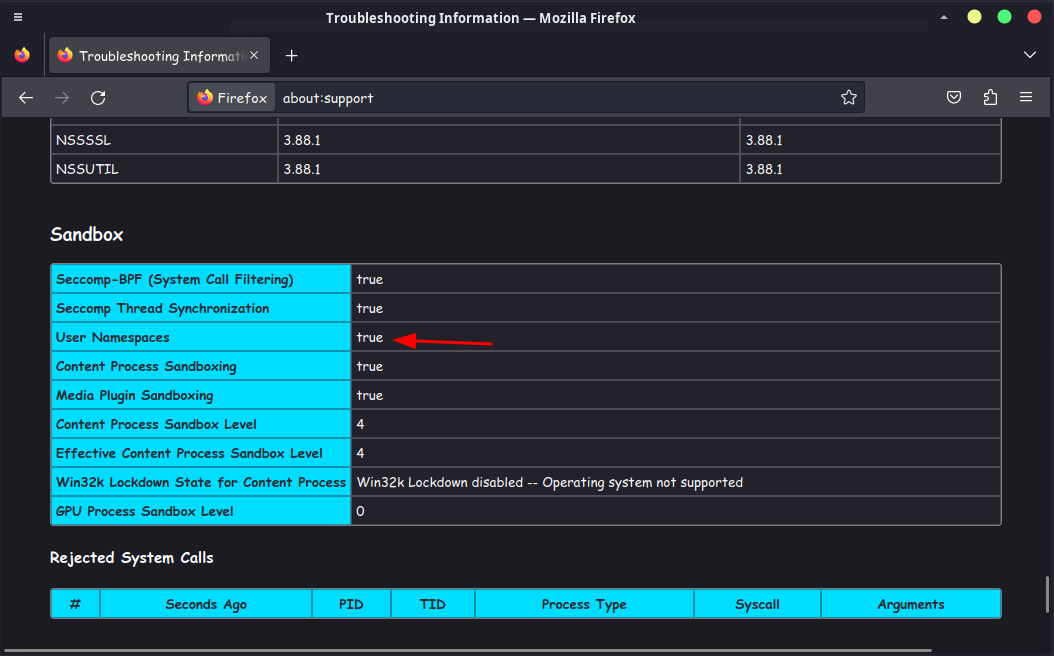

Firefox using user-namespaces sandbox. If your kernel supports the user-namespace feature, it’s activated as an additional protection layer.

Firefox using user-namespaces sandbox. If your kernel supports the user-namespace feature, it’s activated as an additional protection layer.

Limiting access to system resources

Together with the technologies used in the previous step, the seccomp-bpf technology is used in this step. The technologies used in the previous step are not sufficient on their own and are generally used to create a sandbox. seccomp-bpf is used in more detail to filter system calls and restrict system resources.

seccomp-bpf

seccomp-bpf is a security feature that provides protection to programs running on Linux systems. It works by restricting the system calls that a program can make, which reduces the number of attack vectors available to an attacker. Essentially, it limits the amount of interaction a program can have with the underlying system, which makes it harder for attackers to take advantage of system calls to execute malicious code.

With seccomp-bpf, programs can define a list of allowed system calls, and everything else is blocked. This feature can be used to create a filter of sorts that only allows the necessary system calls for a program to run. It is an effective tool in the fight against attacks that exploit system calls for malicious purposes.

This is a feature since Linux kernel 3.5 and is used in both of Firefox and Chromium.

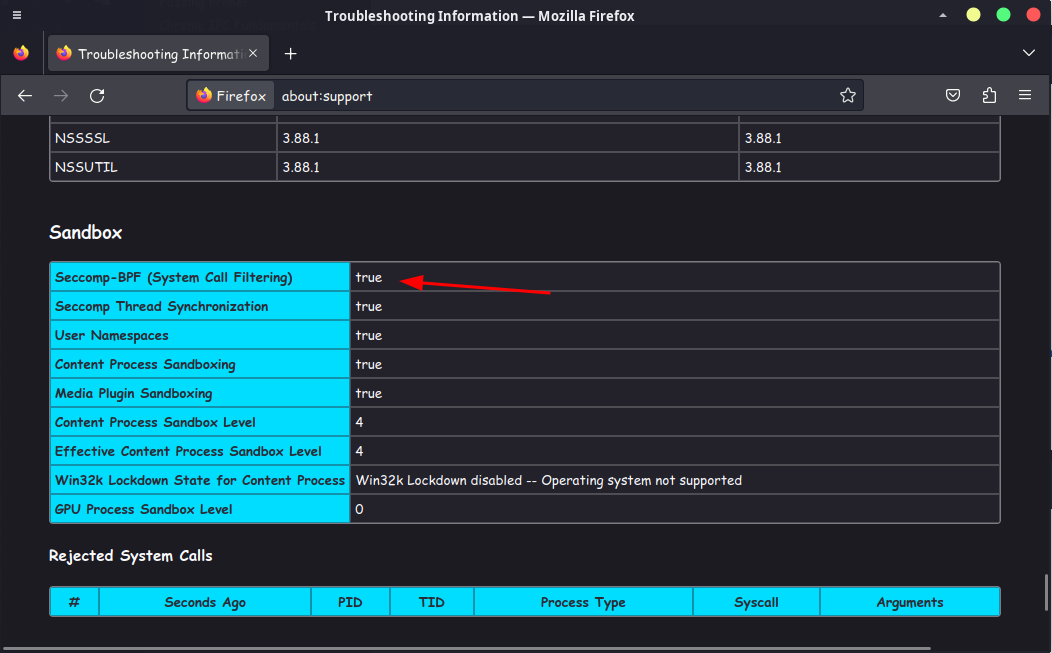

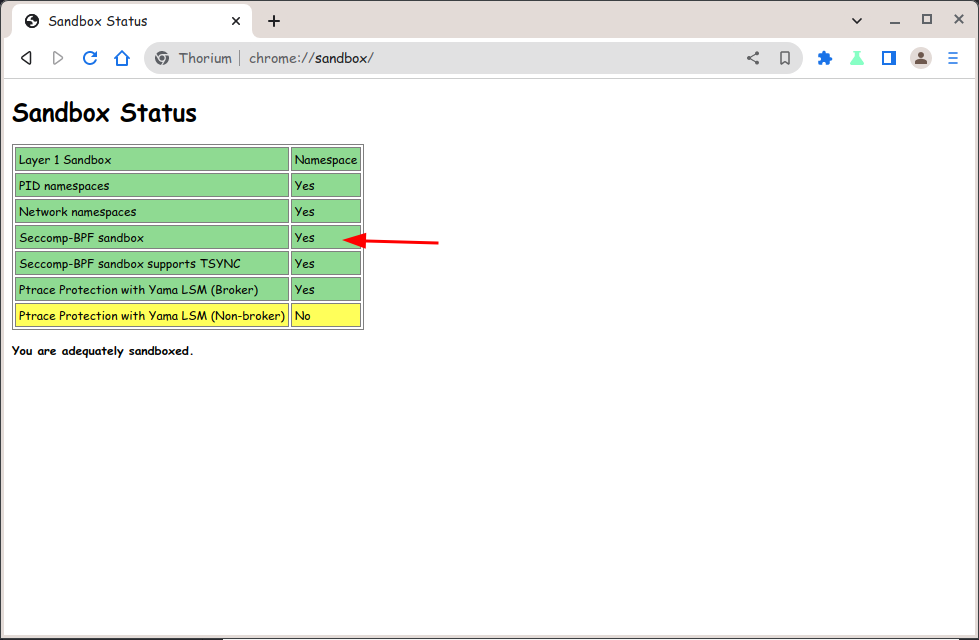

Firefox and Chromium using seccomp-bpf

Firefox and Chromium using seccomp-bpf

Running web content in separate processes

This step of browser protection separates web content into different parts, so the browser is more secure and reliable. If there’s a problem with one part, it won’t affect the whole browser.

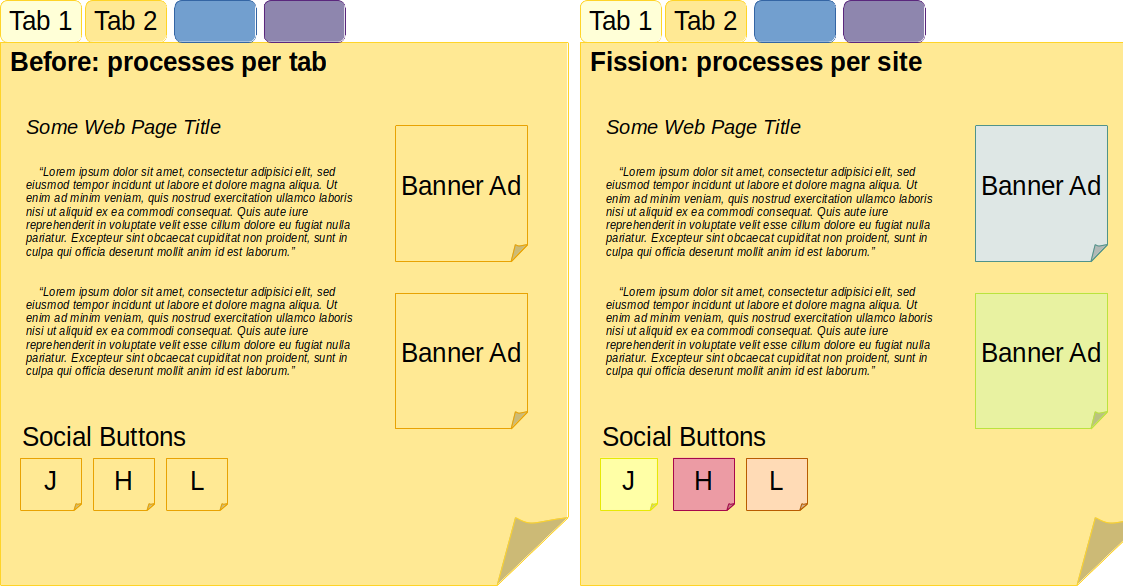

Firefox and Chromium use a way of doing this called multi-process architecture. Firefox has a project called “Electrolysis” or “e10s” that separates the browser parts. Chromium separates every tab and add-on into different parts, and this is called the “Chromium process model”

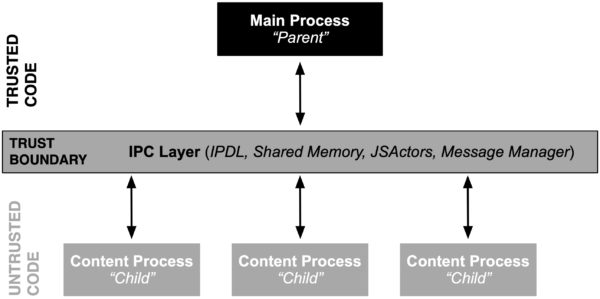

As you can see in the image above, in Firefox’s new sandboxing architecture (Fission), each website is divided into separate processes. This architecture is similar in Chromium as well.

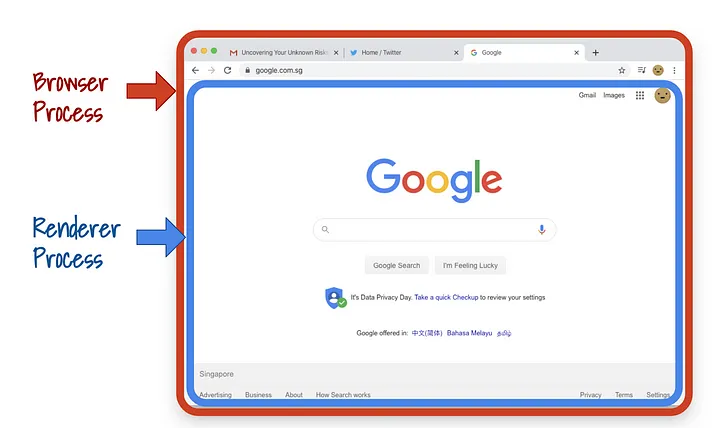

Additionally, with this step, the main browser process is separated from the content processes.

When web content is run in separate processes, it means that if there is a security issue, attackers won’t be able to take control of the entire browser. Also, if there is a problem with one tab, it won’t crash the whole browser.

Monitoring and enforcing security policies

When we separate web content or extensions into unprivileged processes, they cannot directly access system resources. This means that less privileged code will need to ask more privileged code to perform operations which it itself cannot. That request for delegation of operations or in general any communication between content and parent process happens through the IPC Layer.

IPC (inter-process communication)

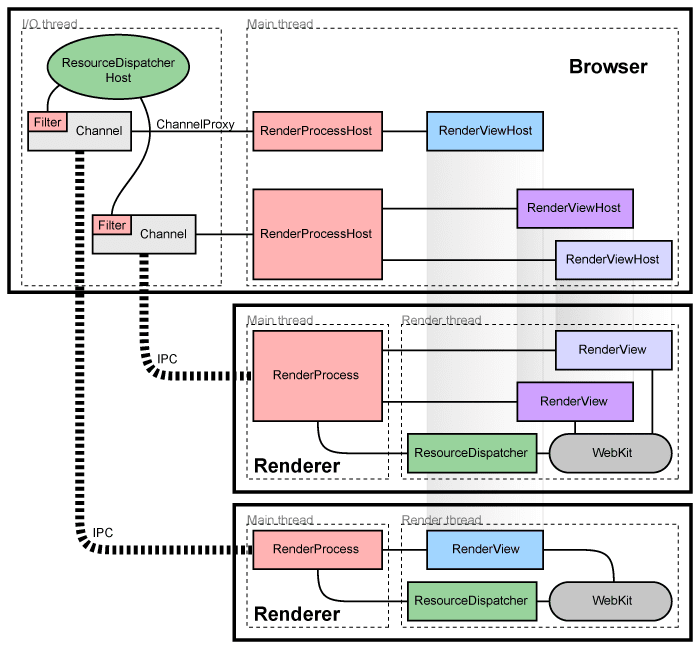

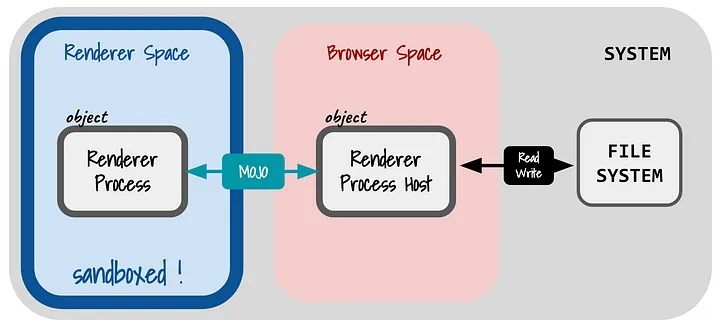

IPC allows different processes to communicate with each other, and it’s commonly used in browser sandboxing to ensure that communication between different browser components is secure and restricted. For example, in Chromium’s multi-process architecture, each renderer process runs in a separate sandbox and communicates with the browser process using IPC mechanisms. The browser process acts as a mediator and enforces security policies to prevent any unauthorized or malicious activity.

Similarly, in Firefox’s Electrolysis project, the browser UI process communicates with the content process using IPC mechanisms. This allows Firefox to enforce security policies and prevent any malicious activity from affecting the user’s system.

An overview of the IPC mechanism in Firefox. Firefox uses IPDL, Shared Memory, JSActors and Message Manager in the IPC layer.

An overview of the IPC mechanism in Firefox. Firefox uses IPDL, Shared Memory, JSActors and Message Manager in the IPC layer.

An overview of the IPC mechanism in Chromium. Chromium uses Mojo for IPC. Mojo is a modern, asynchronous, message-passing framework. Mojo messages can be sent over a variety of transport mechanisms, including shared memory, pipes, and sockets.

An overview of the IPC mechanism in Chromium. Chromium uses Mojo for IPC. Mojo is a modern, asynchronous, message-passing framework. Mojo messages can be sent over a variety of transport mechanisms, including shared memory, pipes, and sockets.

Escaping

I will not specifically address any vulnerability related to escaping from the sandbox here. What I want to point out is that if we want to escape from the sandbox, we need to target which parts of the mechanism and try to find vulnerabilities.

To better understand the potential attack points, let’s use the image above. As you can see, the image is prepared for Chromium, but if we ignore that the name of the IPC layer in the picture is Mojo, there will be no significant difference between Firefox and Chromium in general.

Anyway, if we want to find a vulnerability in the sandbox mechanism and take over the entire browser process, there is a point we can attack, the IPC layer. If we can find any vulnerability in the IPC layer, we can gain full access to the parent process (or the main browser process). This will allow us to access the operating system resources (and, of course, use other operating system vulnerabilities) to access the entire system. Alternatively, if we want, it would be possible to access other browser processes and steal the user’s credentials.

There are many vulnerabilities (or bugs) that target the IPC layer.

In addition, another target that we can attack is the operating system’s sandboxing features. For example, any vulnerability in user-namespaces or in the SUID sandbox can cause an escape from the sandbox.

There are several blog posts explaining how to escape the sandbox using old vulnerabilities:

- https://www.zerodayinitiative.com/blog/2022/8/23/but-you-told-me-you-were-safe-attacking-the-mozilla-firefox-renderer-part-2

- https://googleprojectzero.blogspot.com/2019/04/virtually-unlimited-memory-escaping.html

Additional Notes

Using web browsers in Flatpak

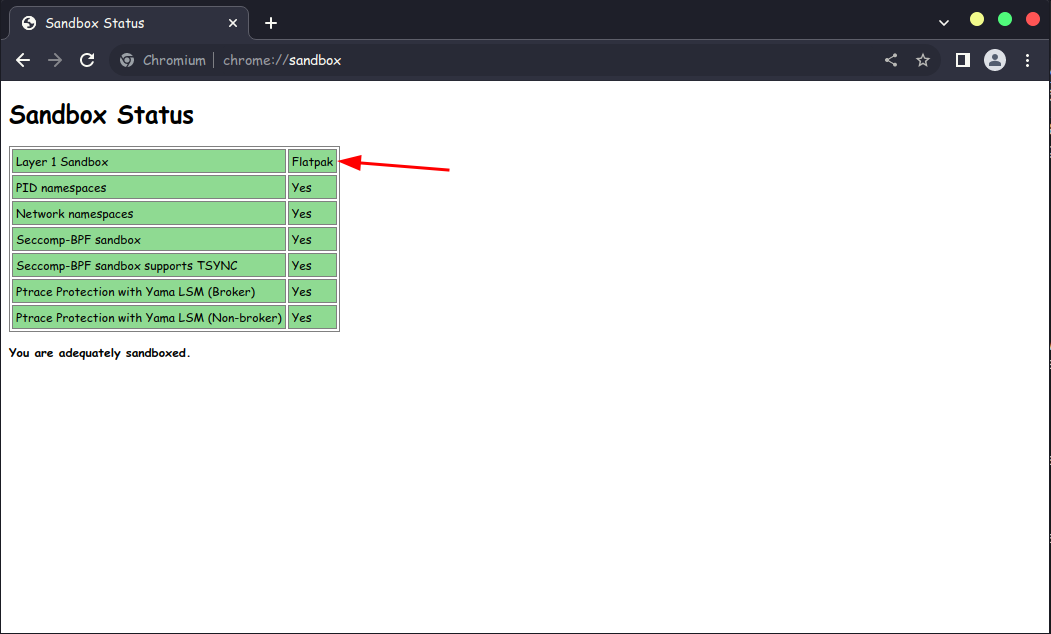

Flatpak is a great technology that allows you to install applications on Linux distributions regardless of the package system. However, using web browsers with Flatpak creates a security risk. This is because Flatpak creates a sandbox environment (using Bubblewrap) and does not allow opening another sandbox inside this sandbox (user-namespaces). The two browsers discussed above (Firefox and Chromium) use user-namespaces sandbox and have a security issue when they cannot open user-namespaces sandbox.

To explain it further, Flatpak replaces its own user-namespaces sandbox for Chromium-based browsers instead of Chromium’s sandbox. A similar situation applies to Firefox. Although there is no direct replacement situation for Firefox, Firefox inside Flatpak cannot create its own user-namespaces sandbox, and Flatpak already has a sandbox environment. As a result, we still have to rely on Flatpak’s own sandbox.

Screenshots from Firefox and Chromium. As you can see, Flatpak does not allow the browsers to use their own sandbox mechanism, and you are forced to use Flatpak’s sandbox mechanism provided by bubblewrap.

Of course, the sandbox provided by Flatpak is also very nice, but I prefer to use sandbox mechanisms specifically designed for browsers rather than a general-purpose sandbox. Additionally, if you’re wondering what happened to Chromium’s SUID sandbox, it can’t be used because bubblewrap sandbox doesn’t allow privilege escalation or SUID bits.

In conclusion, my recommendation is to avoid using browsers as Flatpak applications unless you have a specific need or expectation for it.

Conclusion

Browser sandboxing is an important security measure that helps prevent attackers from exploiting vulnerabilities in web browsers to gain access to a user’s computer or sensitive data. Both Firefox and Chromium utilize sandboxing techniques to isolate web content from the rest of the system. Thanks to sandboxing, any vulnerability found in the renderer process is much less critical and we can still remain secure.

However, as with any security mechanism, there is always the possibility of vulnerabilities that can be exploited to escape the sandbox.

That’s why it’s crucial to keep your browser and operating system up to date and stay informed about security vulnerability news in order to minimize the impact of these vulnerabilities.

Additionally, if you think you have found or are trying to find a vulnerability in the browser sandbox, you can check out the company’s own bug bounty programs. For example, Mozilla has a bug bounty program and vulnerabilities that allow sandbox escape are of the highest priority level.

See Also

- https://wiki.mozilla.org/Security/Sandbox

- https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/src/+/HEAD/docs/linux/sandboxing.md

- https://blog.mozilla.org/attack-and-defense/2021/01/27/effectively-fuzzing-the-ipc-layer-in-firefox/

- https://blog.mozilla.org/attack-and-defense/2021/04/27/examining-javascript-inter-process-communication-in-firefox/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=StQ_6juJlZY

- https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/src/+/HEAD/docs/design/sandbox.md

- https://medium.com/swlh/my-take-on-chrome-sandbox-escape-exploit-chain-dbf5a616eec5

- https://wiki.mozilla.org/Electrolysis

- https://seclab.stanford.edu/websec/chromium/chromium-security-architecture.pdf

- https://powerofcommunity.net/poc2018/ned.pdf

- https://www.chromium.org/developers/design-documents/multi-process-architecture/

- https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/src/+/main/docs/process_model_and_site_isolation.md

- https://www.kernel.org/doc/html/v4.19/userspace-api/seccomp_filter.html

- https://bugzilla.mozilla.org/show_bug.cgi?id=1756236

- https://blogs.gnome.org/wjjt/2021/03/25/chromium-on-flathub/

- https://github.com/refi64/zypak